Trophobiosis: Planthoppers and Their Surprising Partners

Discover how planthoppers form mutualistic bonds with ants, cockroaches, and even geckos. A new study reveals the secrets of trophobiosis, showing unexpected insect partnerships in nature.

In the intricate web of insect relationships, few interactions are as fascinating as trophobiosis—a symbiotic partnership where one organism provides food in exchange for protection or other benefits. While the most well-known examples involve ants tending aphids, a ground-breaking new study titled When Cockroaches Replace Ants in Trophobiosis (Bourgoin et al., 2023) reveals that planthoppers (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha) engage in even more diverse and surprising alliances.

Another article concluded that the most sophisticated ant-homopteran relationships occur in three advanced ant subfamilies: Myrmicinae, Dolichoderinae, and Formicinae. These ants have evolved specialized farming behaviors, while their homopteran partners (including planthoppers) developed unique adaptations. Unlike lycaenid butterflies that secrete nutrients from glands, homopterans provide honeydew – a digestive byproduct rich in:

- 90-95% carbohydrates (including unique sugars like melezitose)

- 0.2-1.8% nitrogen compounds (mostly amino acids)

- Organic acids, B-vitamins, and minerals

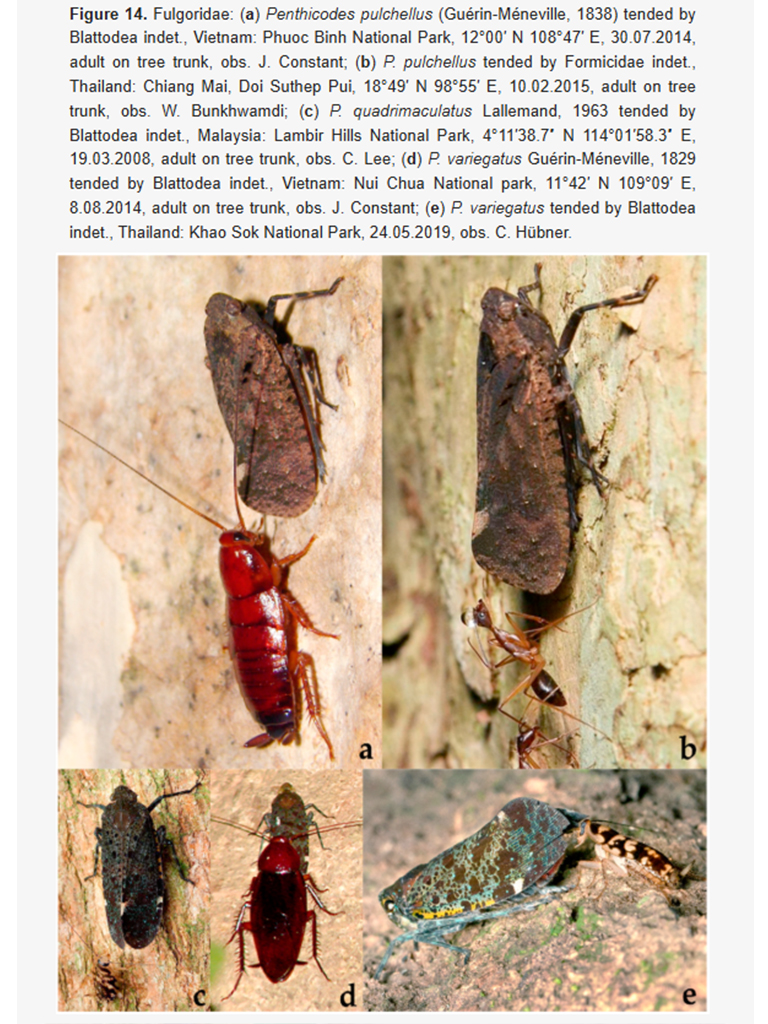

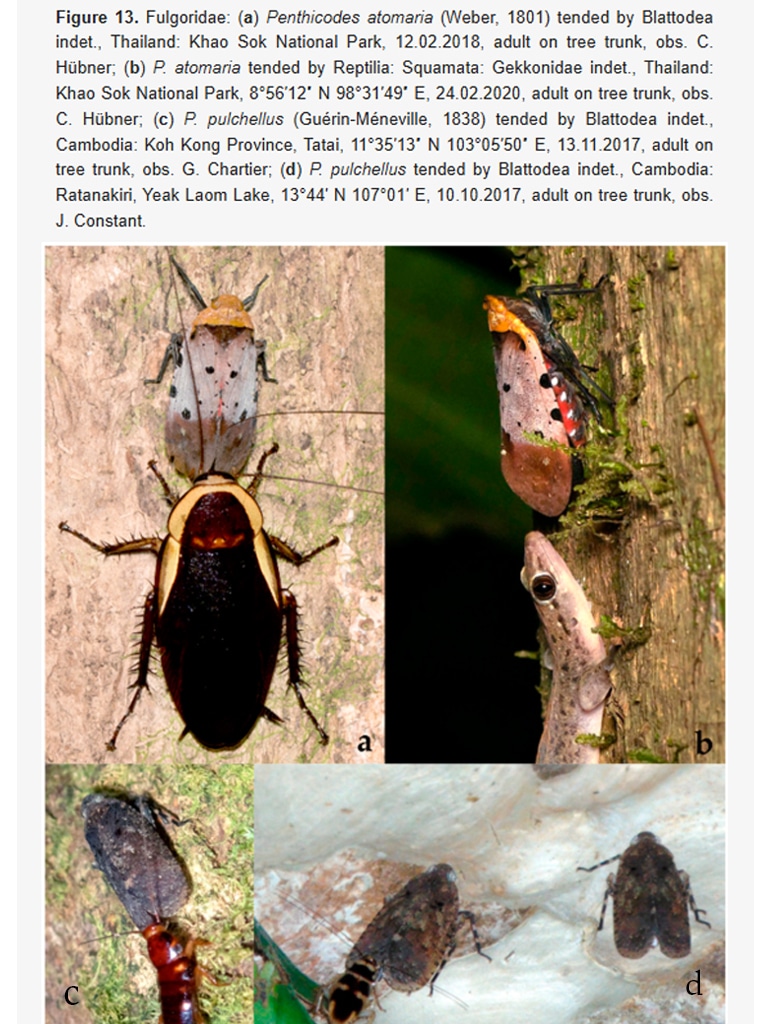

This research, published in Diversity, compiles 267 documented cases of trophobiosis involving planthoppers, including 126 new observations. The findings challenge long-held assumptions about these relationships, showing that cockroaches, geckos, moths, and even snails can act as “xenobionts” (hosts) that feed on planthopper honeydew.

What Exactly Is Trophobiosis?

Trophobiosis is a form of mutualism where a trophobiont (in this case, planthoppers) secretes honeydew—a sugary, nutrient-rich liquid—that is harvested by another organism. The relationship can be:

- Occasional (short-term): Brief interactions where xenobionts opportunistically feed on honeydew.

- Long-term mutualism: Some ants actively protect planthoppers, even relocating them to nests (cryptobiotic species) or allowing them to remain free (optobiotic species).

This behavior is well-documented in ants and hemipterans (like aphids and scale insects), but Bourgoin et al.’s study highlights how understudied planthopper interactions have been—until now.

Unexpected Partners Beyond Ants

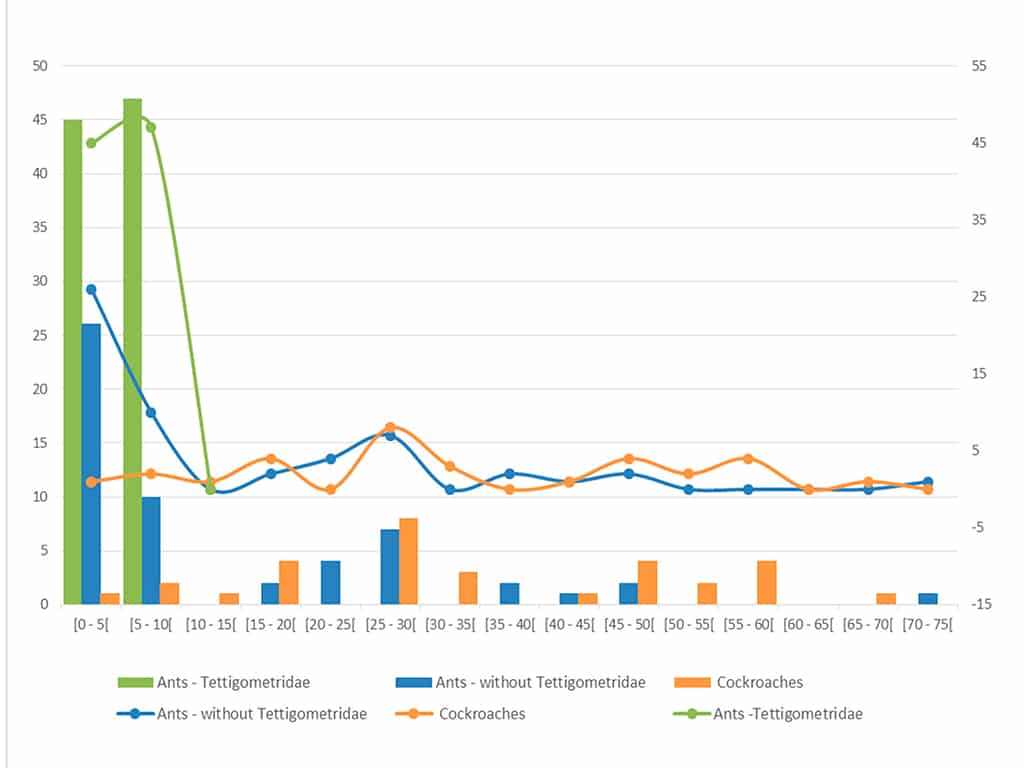

While ants remain the most common xenobionts (77% of cases), the study reveals surprising alternative partners:

- Cockroaches (13%)

- Large planthoppers (e.g., Fulgoridae) are frequently tended by cockroaches (40% of Fulgorid cases).

- Unlike ants, cockroaches tap the planthopper’s wings with their maxillary palps, possibly stimulating honeydew release.

- Example: Pyrops whiteheadi (a lanternfly) was observed being attended by multiple cockroach species in Southeast Asia.

While cockroaches mimic ant tending behaviors, they lack the sophisticated farming seen in advanced ant subfamilies. Unlike ants that may groom partners for hours, cockroaches engage in brief, opportunistic interactions.

- Geckos (6%)

- Small geckos (e.g., Hemidactylus platyurus) have been seen licking honeydew directly from planthoppers.

- Some geckos even tap the tree bark to encourage honeydew production—a behavior first documented in Madagascar.

- Moths and Snails

- Moths (Nolidae, Erebidae) were observed tapping planthoppers with their antennae.

- Snails (e.g., Euglandina) position themselves to catch honeydew mid-air, a behavior first reported by Naskrecki & Nishida (2007).

Key Discoveries from the Study

- Size is important

- Larger planthoppers (like Fulgoridae) are more likely tended by cockroaches, possibly because they produce more honeydew.

- Smaller species (e.g., Tettigometridae) are almost exclusively ant-attended.

- Behavioral Strategies

- Ants use antennal palpation to stimulate honeydew release.

- Cockroaches rely on wing-tapping.

- Geckos use vibrations to “ask” for honeydew.

- Tettigometridae – The Ultimate Ant Partners

- 32 of 92 known Tettigometridae species (35%) engage in trophobiosis, often with ants.

Some species live underground in ant nests, while others are guarded on plants.

Why This Research Matters

- Ecological Insights

- Trophobiosis plays a crucial role in food webs, influencing predator-prey dynamics and nutrient cycling.

- Understanding these relationships helps explain insect biodiversity and coevolution.

- Citizen Science & Photography

- Many observations came from wildlife photographers and amateur entomologists, proving the value of public contributions to science.

- Agricultural Implications

- Some planthoppers are pests, and their mutualisms with ants can complicate pest control.

- Knowing which species rely on trophobiosis could help develop eco-friendly management strategies.

Related Research

- Naskrecki & Nishida (2007) – First documented snail-planthopper trophobiosis.

- Way (1963) – Classic work on ant-hemipteran mutualisms.

- Compton & Robertson (1988) – Showed how ant-tended planthoppers can indirectly benefit plants by deterring herbivores.

Conclusion

The study When Cockroaches Replace Ants in Trophobiosis reshapes our understanding of insect symbioses, revealing that planthoppers form partnerships with a far wider range of species than previously thought. From cockroaches to geckos, these interactions highlight nature’s creativity in forging survival strategies.

Thumbnail image by C. Lee

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/49399703