Network analysis: methods for studying microbial communities

Microbial communities, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, protists, and archaea, thrive in complex environments where they engage in numerous inter- and intra-kingdom interactions. These interactions play a critical role in ecosystem functioning, nutrient cycling, and human health.

Microbial communities, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, protists, and archaea, thrive in complex environments where they engage in numerous inter- and intra-kingdom interactions. These interactions play a critical role in ecosystem functioning, nutrient cycling, and human health. Understanding these relationships is essential for advancing fields such as medicine, agriculture, and environmental science. Network-based approaches have emerged as powerful tools for deciphering these complex microbial interactions, offering insights into co-occurrence patterns and ecological dynamics.

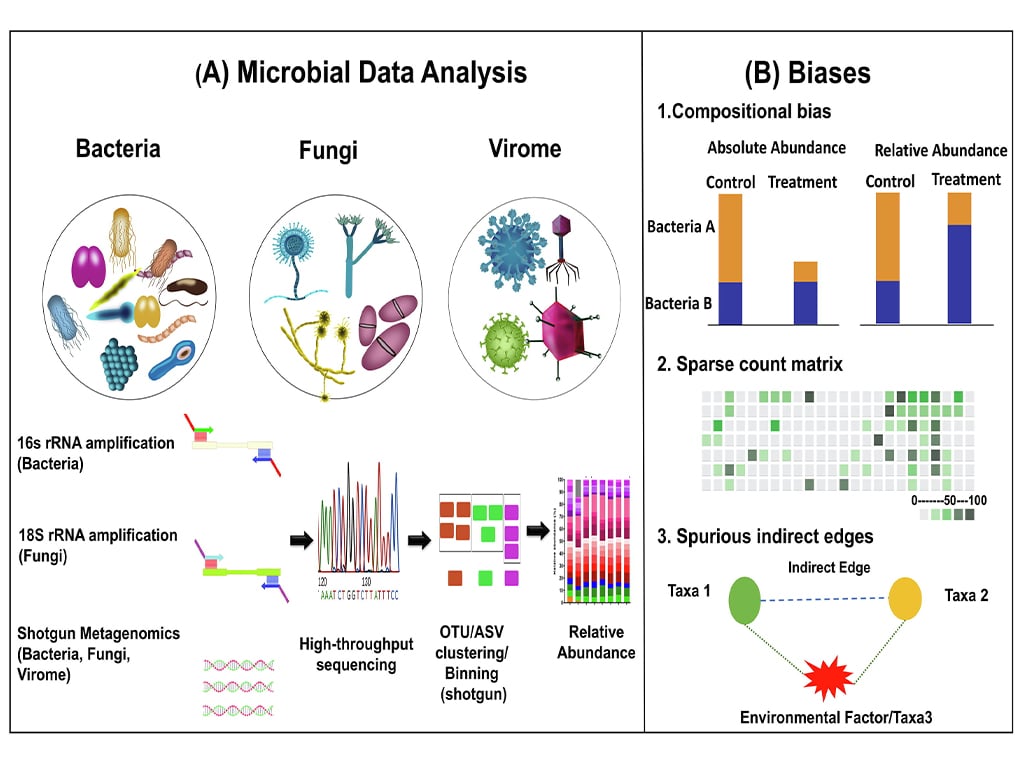

Figure 1: A schematic overview of taxonomic profiling for bacteria, fungi, and the virome using techniques like 16S rRNA gene sequencing, ITS sequencing, and shotgun metagenomics.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of state-of-the-art methods for inferring microbial interactions, focusing on intra-kingdom relationships. The methods range from simple correlation-based techniques, such as Pearson and Spearman correlation, to more advanced conditional dependence models like probabilistic graphical models and Gaussian graphical models. Each method has its strengths and weaknesses, with trade-offs in accuracy, computational complexity, and scalability.

One of the main challenges in microbial network analysis is addressing biases such as compositionality, sparsity, and spurious correlations. Compositionality arises because microbial data represent relative abundances rather than absolute counts, leading to misleading correlations. Sparsity refers to the high number of zero counts in datasets, which can result from low sequencing depth or the absence of certain taxa. Spurious correlations occur when indirect interactions are misinterpreted as direct ones.

To mitigate these challenges, researchers employ various strategies. For example, centered log ratio transformation (CLR) is widely used to address compositionality by transforming relative abundances into a more interpretable format. Probabilistic graphical models and regularization techniques, such as lasso regression, help distinguish direct interactions from indirect ones. However, these methods often come with increased computational complexity.

Figure 2: A visual summary of the different network analysis methods, including correlation-based methods, conditional dependence models, and trans-kingdom analysis tools.

The article also highlights the importance of computational tools for inferring microbial interaction networks and their applications in studying diverse environments, such as the human gut, oral cavity, and soil microbiomes. These tools have been instrumental in identifying key microbial interactions and understanding their roles in health and disease. For instance, network analysis has revealed microbial biomarkers associated with conditions like inflammatory bowel disease and obesity.

Emerging methods for trans-kingdom interactions and multi-omics data integration are also discussed. While most existing tools focus on intra-kingdom interactions, particularly among bacteria, there is a growing need to study interactions across kingdoms, such as between bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Methods like multi-omics factor analysis (MOFA) and data integration analysis for biomarker discovery using latent components (DIABLO) are paving the way for integrative analyses of multi-modal data.

Figure 3: A workflow to help researchers choose the appropriate network analysis method based on specific challenges, such as compositionality, sparsity, and trans-kingdom interactions.

Despite these advances, challenges remain. Current methods often struggle with scalability, especially when dealing with large datasets containing thousands of taxa and samples. Additionally, the interpretation of network results can be complicated by the presence of indirect interactions and confounding factors. Future research should focus on developing more robust and scalable methods for trans-kingdom interactions, validating findings with experimental studies, and creating universal benchmark datasets for method evaluation.

In conclusion, network analysis is a powerful tool for understanding microbial communities, but there is still much to learn. Future efforts should prioritize the integration of multi-omics data, the development of methods for studying dynamic interactions over time, and the validation of network predictions through experimental approaches. By addressing these challenges, researchers can unlock the full potential of microbial network analysis and gain deeper insights into the complex world of microbial ecosystems.